Disclaimer: I am not a medical professional. Do not ingest or otherwise use a herb or oil based on this information. Always do your own research, and speak with a medical professional about the supplements that you are taking. Wild Hemlock takes no responsibility of how you use this information. Herbs on this website may not be approved by the FDA nor may be on the Generally Regarded as Safe list of herbs maintained by the FDA. This information has not been evaluated by the FDA. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

Pinene is one of the most abundant terpenes found in plants. It is a powerhouse of natural healing and home remedies. It has two isomers, labeled alpha and beta, and two enantiomers, labeled positive and negative. These properties allow for a varied abundance of medically significant uses.

Alpha- and Beta-Pinene are terpenes which are present in many different plant species across the world. Most notably, these chemicals are what give the pine tree its distinct smell. Although named for the evergreen trees that contain a high percentage of these terpenes, α-Pinene (alpha-Pinene) is the most abundant terpene found in nature [2]. Forms of these compounds have been used medically for thousands of years and have even been prescribed by Hippocrates himself, but that does not mean they are entirely safe [4].

Terpenes are the most populous type of chemicals found in natural sources. Most terpenes are created by plants, but some complicated ones are formed in animals. In plants, they are used for many reasons: to attract insects, to repel insects, to poison predators, and more. It is more useful to categorize terpenes by their chemistry than by their uses, because of how many plant compounds are terpenes [7].

Chemistry of Pinene

Terpenes have quite interesting chemistry. They are lipid (meaning non-polar, like oils) hydrocarbons, which are characterized by their isoprene structure. This means that they mostly consist of carbon and hydrogen atoms. These atoms are grouped together in units of 5 carbon atoms plus hydrogen. Two isoprene units makes one monoterpene. Both α-pinene and β-pinene (beta-pinene) are monoterpenes, and are considered irregular monoterpenes because their chemical structure does not follow the “isoprene rule” – or link up the same way as most other terpenes [7].

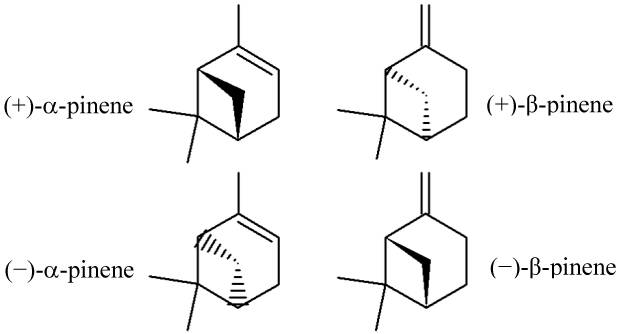

α-pinene and β-pinene are two isomers of Pinene. This means that both α- and β-pinene have the same chemical formula, C10H16 [6][8], but their chemical bonds have two different structures. α- and β-pinene also have two enantiomers each as well, (+)-α-pinene and (-)-α-pinene; (+)-β-pinene and (-)-β-pinene [3]. Enantiomers are pairs of molecules which are “mirror images” of each other – they have the same properties yet emit light backwards from each other, giving us evidence that they have the opposite, or mirrored, molecular structure [9].

The Isomers and Enantiomers of Pinene, da Silva Rivas, Ana Cristina et al. [3]

These slight differences matter, because (-)-α-pinene is mainly found in European pines, while (+)-α-pinene is a constituent of most American pines. For example, positive α-pinene shows a much, much higher rate of antimicrobial activity than negative α-pinene [3].

This means that Pinene is not two but four different chemicals.

Benefits of Pinene

Clinical studies have observed benefits of using α-pinene and β-pinene over a large array of therapeutic areas. While other studies are extremely valuable, the in vivo clinical trials are the most useful in determining what these terpenes can truly do. These studies fall under a handful of beneficial categories: anti-cancer*, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, and anti-Alzheimer’s* activity [1]. In vitro, animal, and small studies demonstrate even more benefits of these terpenes.

Clinical Benefits

Anti-Cancer* – Liver hepatoma carcinoma tumor growth was suppressed when treated directly with α-pinene isolated from the pine needles of Pinus massoniana. It is believed that it enhances DNA’s damage response abilities [1]. Animal tests on melanoma had mixed results [1].

Anti-Allergic – α-pinene administered to humans revealed inhibition of allergic response. This, in turn, reduced the immune and inflammatory response caused by seasonal allergens [1].

Anti-Inflammatory – (+)-α-pinene from the Juniperus oxycedrus tree was able to suppress inflammation linked to the IL-1β pathway in human tests [1]. Additionally, α-pinene was shown to inhibit TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production during acute pancreatitis [1] [24].

Anti-Microbial – Studies with both α-pinene and β-pinene have affirmed anti-microbial activity. Isolated α-pinene has been effective against MRSA, B. cereus, E. coli, and Campylobacter jejuni. When included in Tea Tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) essential oil, pinene is also effective against S. aureus, S. edipermidis, and Propionibacterium acnes (facial acne) [1]. Ironwort or Mountain Tea (Sideritis erythrantha) essential oil contains 27-28% (+)-α-pinene and (+)-β-pinene combined, and have effectiveness against MRSA, Enterococcus faecalis, Haemophilus influenzae, and C. albicans [1] [3].

Anti-Alzheimer’s* – Spanish Sage (Salvia lavandulaefolia), consisting of 6.5% α-pinene and 5.4% β-pinene among other terpenes, has been utilized in double blind studies pertaining to adults with Alzheimer’s dementia. Both control and Alzheimer’s positive groups demonstrated marked improvement in mood, cognition, and memory [1]. Additionally, S. lavandulaefolia and S. officinalis (Common Sage) have been reported to inhibit enzymes associated with Alzheimer’s [1].

* Never rely on herbal remedies to fight a serious disease, and speak to your doctor about any and all herbal supplements you take or wish to try. Please read warning at the beginning of article.

There are a number of other benefits that are associated with α-pinene and β-pinene, but do not have any large scale human trials. That does not mean that the information is untrue however, it is not as confirmed as the above uses.

Small Trial, Animal Study, or In Vitro Benefits

Pinene in Nature

Pinene is abundant in nature, found all around the world. The number one place to look is its namesake, the Pine tree. Many conifer trees, although not true pines, also contain high levels of pinene. The following are the plants with the highest concentration of pinene: pines, nutmeg, rosemary, black pepper, sage, and hemp [10] [11].

Pine Trees

Pine trees are the most abundant source of both α-pinene and β-pinene. Depending on the species, pine resin can contain up to 80% α-pinene (Pinus gerardiana) and up to 20% β-pinene (Pinus sylvestris) [10] [11]. Pine needle extract has been shown to inhibit the iNOS, IL-6, and IL-1β inflammatory response [25]. Pine needle essential oil has been used in a small number of clinical trials. These trials support its use as an anti-bacterial, anti-oxidant, and anti-fungal [26]. When paired with eucalyptus and menthol, pine needle oil is a proven remedy for upper respiratory infections [26]. Anti-tumor activity has been observed in mice trials [27].

Balsam Fir essential oil contains up to 25.8% α-pinene and 27.3% β-pinene [47]. I use those benefits in my Mountain Lion Balm, a powerful natural pain killer.

Nutmeg

Nutmeg, or Myristica fragrans, is an evergreen tree which is cultivated for its seeds (nutmeg) and seed covering (mace). The essential oil of the nutmeg seed contains between 10.6 – 26.5% α-pinene and 8 – 15% β-pinene [28]. A large amount of nutmeg can induce a toxic overdose with hallucinations and rarely death [29]. Anti-microbial effects have been noted both in vitro and as an insecticide on plants [29]. Nutmeg fruit has been shown to decrease inflammation by decreasing COX-2, TNF-α and IL-6 [30]. Nutmeg has been successfully studied for its liver protective ability [31] and anti-oxidant effects [29].

Rosemary

Rosmarinus officinalis, or Rosemary, is a common kitchen herb that is used fresh or dried in many dishes. Its essential oil contains up to 25% α-pinene and between 3.4 – 8% β-pinene [32]. Rosemary has a plethora of different medical benefits, from hair loss studied in humans [33] to prostate cancer studied in mice [34]. It is both an antioxidant and hepatoprotective (protective of the liver) [35]. It is an anti-inflammatory [36] as well as an effective anti-bacterial [37]. Components of rosemary have been demonstrated to improve memory in mice models of Alzheimer’s disease and helps prevent neurotoxicity [38].

Black Pepper

Black Pepper, or Piper nigrum, is a common spice used in all types of dishes and genres of cooking. Despite the guilt by association it suffers from due to its frequent pairing with salt, pepper is very healthy. Its oil contains between 4.5 – 9.4% α-pinene and 8.5 – 13.8% β-pinene [39]. Black pepper has been used in the ancient traditional medicine of China, Thailand, India, and the Middle East for rheumatism, pain, asthma, cancer, and gastric and respiratory disorders [40]. Today we know that black pepper is an effective food preservative through anti-microbial and anti-oxidant means, as well as an effective anti-inflammatory [40]. In mice and rats, anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory and anti-Alzheimer’s activities have been demonstrated [40]. Another Piper plant known as Kava, or Piper methysticum, has been shown in clinical trials to be an effective anti-anxiety supplement [40].

Common Sage

Sage is one of the oldest medicinally used plants for cognitive enhancement and has evolved into a synonym for “wise”. Salvia officinalis contains 1.1 – 5% α-pinene and 1.1 – 5.5% β-pinene [43]. During a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled human study, Sage essential oil has demonstrated statistically significant improvements in cognitive function in adults with Alzheimer’s disease [42]. It is believed that the sage plant creates a “perfect storm” against Alzheimer’s – it protects cells from amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity, enhances cholinergic signalling, prevents a decreates in brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and is anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-depressant and anxiolytic [42]. Additionally, sage has demonstrated positive effects against diabetes and other metabolic diseases [44].

Hemp

Cannabis sativa (also Cannabis indica) is the name of the Hemp plant. It has gone by many different names but today is is mainly known as Hemp, Cannabis, or CBD. Hemp contains endocannabinoids as well as terpenes such as α-pinene (2.3 – 16.5% in essential oil) and β-pinene (0.6 – 4.9% in essential oil) [22]. Scientists are still determining all of the medical benefits of the hemp plant, so research is going to be slow for another few years. Current human trials in older adults show promise for conditions like pain management, chronic pain, and neuropathic pain [46]. More studies are underway to determine its effectiveness against sleep disorders, Parkinson’s disease, nausea, post-traumatic stress disoder, and both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s dementia [45].

Honorary Mentions

| Plant and Part | α-pinene | β-pinene |

| Tea Tree, Melaleuca alternifolia Essential Oil [41] | 2.3 – 2.4% | 0.7 – 1.6% |

| Dill, Anethum graveolens Essential Oil [13] | 1.75 – 3.17% | 1.36% |

| Lemon Eucalyptus, Eucalyptus citriodora Essential Oil [14] | 0.29 – 0.6% | 1.16 – 1.7% |

| Celery, Apium graveolens Essential Oil, Root and Stem [15] | 1 – 1.8% | 0.5 – 1.5% |

| Cardamom, Elettaria cardamomum Essential Oil, Seed [16] | 1.2 – 1.6% | 0.4 – 2.6% |

| Valerian Root, Valeriana officinalis Essential Oil, Root [17] | 0.1 – 0.6% | 0.5 – 4.3% |

There are many ways to use these plants, and by extention, pinene. Make sure to do your research about the specific plants and the specific reason you wish to use them. The following sources are a great place to start.

* Never rely on herbal remedies to fight a serious disease, and speak to your doctor about any and all herbal supplements you take or wish to try. Please read warning at the beginning of article.

Do you like WildHemlock.Com?

Support with Paypal!

Sources:

- Salehi, Bahare et al. “Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene: A Miracle Gift of Nature.” Biomolecules vol. 9,11 738. 14 Nov. 2019, doi:10.3390/biom9110738 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6920849/>

- Noma, Yoshiaki, and Yoshinori Asakawa. “Biotransformation of Monoterpenoids.” Comprehensive Natural Products II, vol. 3, 2010, pp. 669–801., doi:10.1016/b978-008045382-8.00742-5. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/alpha-pinene>

- da Silva Rivas, Ana Cristina et al. “Biological Activities of α-Pinene and β-Pinene Enantiomers.” Molecules vol. 17,6 6305–6316. 25 May 2012, doi:10.3390/molecules17066305 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6268778/>

- Shahrokh, Soroush & Mazoki, Kristen & Rossi, Garrett. (2020). Expecting the Unexpected: When Use of Complementary Alternative Medicine Goes Wrong. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 15. 15-17. 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2020.150306. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339748939_Expecting_the_Unexpected_When_Use_of_Complementary_Alternative_Medicine_Goes_Wrong>

- Tisserand, Robert, and Rodney Young. “Constituent Profiles.” Essential Oil Safety, 2014, pp. 483–647., doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-06241-4.00014-x. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/beta-pinene>

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. alpha-Pinene, CID=6654, 26 April 2020. <https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/alpha-Pinene>

- “25.6: Terpenes and Terpenoids.” Chemistry LibreTexts, Nassau Community College, 3 Sept. 2019, <https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Nassau_Community_College/Organic_Chemistry_I_and_II/25%3A_Lipids/25.6%3A_Terpenes_and_Terpenoids>

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Database. beta-Pinene, CID=14896, 26 April 2020. <https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/beta-Pinene>

- Schaller, Chris P. “Enantiomers.” Chemistry LibreTexts, 5 June 2019 <https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Organic_Chemistry)/Fundamentals/Isomerism_in_Organic_Compounds/Enantiomers>

- “Alpha-Pinene.” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/chemicals/show/3626>

- “Beta-Pinene.” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/chemicals/show/4706>

- Hou, Jing et al. “α-Pinene Induces Apoptotic Cell Death via Caspase Activation in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells.” Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research vol. 25 6631-6638. 4 Sep. 2019, doi:10.12659/MSM.916419 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6743669/>

- “Anethum graveolens (Apiaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/139>

- “Eucalyptus citriodora (Myrtaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/830>

- “Apium graveolens (Apiaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/160>

- “Elettaria cardamomum (Zingiberaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/733>

- “Valeriana officinalis (Valerianaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/2073>

- de Sousa, Damião Pergentino. “Analgesic-like activity of essential oils constituents.” Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 16,3 2233-52. 7 Mar. 2011, doi:10.3390/molecules16032233 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6259660/>

- Kovač, Jasna et al. “Antibiotic resistance modulation and modes of action of (-)-α-pinene in Campylobacter jejuni.” PloS one vol. 10,4 e0122871. 1 Apr. 2015, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122871 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4382180/>

- Saldanha, Elroy, et al. “Health Effects of Various Dietary Agents and Phytochemicals (Therapy of Acute Pancreatitis).” Therapeutic, Probiotic, and Unconventional Foods, 2018, pp. 303–314., doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814625-5.00016-9. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/alpha-pinene>

- Wang, Ze-Jun, and Thomas Heinbockel. “Essential Oils and Their Constituents Targeting the GABAergic System and Sodium Channels as Treatment of Neurological Diseases.” Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 23,5 1061. 2 May. 2018, doi:10.3390/molecules23051061 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6099651/>

- Mediavilla, Vito, and Simon Steinemann. “Essential Oil of Cannabis Sativa L. Strains.” Journal of the International Hemp Association, vol. 4, no. 2, 1997, pp. 80–82. <http://druglibrary.net/olsen/HEMP/IHA/jiha4208.html>

- Pinheiro, Marcelo de Almeida et al. “Gastroprotective effect of alpha-pinene and its correlation with antiulcerogenic activity of essential oils obtained from Hyptis species.” Pharmacognosy magazine vol. 11,41 (2015): 123-30. doi:10.4103/0973-1296.149725 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4329611/>

- Cho, Kyoung Sang et al. “Terpenes from Forests and Human Health.” Toxicological research vol. 33,2 (2017): 97-106. doi:10.5487/TR.2017.33.2.097 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5402865/>

- Venkatesan, Thamizhiniyan et al. “Pinus densiflora needle supercritical fluid extract suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators iNOS, IL-6 and IL-1β, and activation of inflammatory STAT1 and STAT3 signaling proteins in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-challenged murine macrophages.” Daru : journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences vol. 25,1 18. 4 Aug. 2017, doi:10.1186/s40199-017-0184-y <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5544993/>

- “Pine Needle Oil Uses, Benefits & Dosage – Drugs.com Herbal Database.” Drugs.com, 23 Dec. 2019, <https://www.drugs.com/npp/pine-needle-oil.html>

- Ren, Peng et al. “Frankincense, pine needle and geranium essential oils suppress tumor progression through the regulation of the AMPK/mTOR pathway in breast cancer.” Oncology reports vol. 39,1 (2018): 129-137. doi:10.3892/or.2017.6067 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5783593/>

- “Myristica fragrans (Myristicaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/1355>

- “Nutmeg Uses, Benefits & Dosage – Drugs.com Herbal Database.” Drugs.com, 3 July 2019, <https://www.drugs.com/npp/nutmeg.html>

- Mueller M., Hobiger S., Jungbauer A. Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from fruits, herbs and spices. Food Chem. 2010;122:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.041. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814610003158>

- Morita, Tatsuya et al. “Hepatoprotective effect of myristicin from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) on lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced liver injury.” Journal of agricultural and food chemistry vol. 51,6 (2003): 1560-5. doi:10.1021/jf020946n <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12617584/>

- “Rosmarinus officinalis (Lamiaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/1719>

- “Rosemary Uses, Benefits & Dosage – Drugs.com Herbal Database.” Drugs.com, 22 Oct. 2019, <https://www.drugs.com/npp/rosemary.html>

- Petiwala, Sakina M et al. “Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) extract modulates CHOP/GADD153 to promote androgen receptor degradation and decreases xenograft tumor growth.” PloS one vol. 9,3 e89772. 5 Mar. 2014, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089772 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3943728/>

- Rašković, Aleksandar et al. “Antioxidant activity of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oil and its hepatoprotective potential.” BMC complementary and alternative medicine vol. 14 225. 7 Jul. 2014, doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-225 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4227022/>

- Justo, Oselys Rodriguez et al. “Evaluation of in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of crude ginger and rosemary extracts obtained through supercritical CO2 extraction on macrophage and tumor cell line: the influence of vehicle type.” BMC complementary and alternative medicine vol. 15 390. 29 Oct. 2015, doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0896-9 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4625945/>

- Sienkiewicz, Monika et al. “The potential of use basil and rosemary essential oils as effective antibacterial agents.” Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 18,8 9334-51. 5 Aug. 2013, doi:10.3390/molecules18089334 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6270641/>

- Andrade, Stephanie et al. “Natural Compounds for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy: A Systematic Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 20,9 2313. 10 May. 2019, doi:10.3390/ijms20092313 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6539304/>

- “Piper nigrum (Piperaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/1523>

- Salehi, Bahare et al. “Piper Species: A Comprehensive Review on Their Phytochemistry, Biological Activities and Applications.” Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 24,7 1364. 7 Apr. 2019, doi:10.3390/molecules24071364 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6479398/>

- “Melaleuca alternifolia (Myrtaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/1267>

- Lopresti, Adrian L. “Salvia (Sage): A Review of its Potential Cognitive-Enhancing and Protective Effects.” Drugs in R&D vol. 17,1 (2017): 53-64. doi:10.1007/s40268-016-0157-5 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5318325/>

- “Salvia officinalis (Lamiaceae).” Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, National Agricultural Library, USDA. 1992, <https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/1749>

- Jakovljević, Martina et al. “Bioactive Profile of Various Salvia officinalis L. Preparations.” Plants (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 8,3 55. 6 Mar. 2019, doi:10.3390/plants8030055 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6473381/>

- Abuhasira, Ran et al. “Medical Cannabis for Older Patients-Treatment Protocol and Initial Results.” Journal of clinical medicine vol. 8,11 1819. 1 Nov. 2019, doi:10.3390/jcm8111819 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6912698/>

- Andreae, Michael H et al. “Inhaled Cannabis for Chronic Neuropathic Pain: A Meta-analysis of Individual Patient Data.” The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society vol. 16,12 (2015): 1221-1232. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.009 <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4666747/>

- Josette Ross, Hélène Gagnon, Damien Girard & Jean-Marie Hachey (1996) Chemical Composition of the Bark Oil of Balsam Fir Abies balsamea (L.) Mill., Journal of Essential Oil Research, 8:4, 343-346, DOI: 10.1080/10412905.1996.9700636 <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10412905.1996.9700636>